Natural Killer Cells

Natural killer cells

are part of the innate immune system and are important in fighting intra-cellular

pathogens. In mouse experiments, a mouse lacking both B and T cells can resist

Listeria infection (which is caused by an intracellular bacteria) for a number

of weeks but if the NK cells are depleted it will die from Listeria infection

very quickly. Although this ability to kill viruses without antigen specificity

is impressive it is not likely to be physiologically important in humans.

An absence of NK cells is very rare but those individuals who do lack NK cells

have essentially no immunocompromise, only being more susceptible to the early

stages of herpes virus infections.

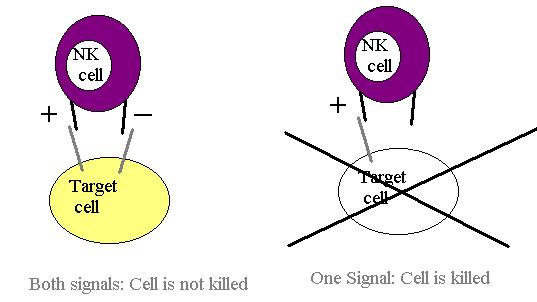

Natural Killer cells are lymphocytes that lack antigen specificity and thus they must rely on some other mechanism to kill virally infected cells. This mechanism depends on the presence of two receptors on the surface of the NK cell. These are NKR-P1 and Ly49. NKR-P1 binds to host cell carbohydrates, triggering the NK cell to kill the host cell to which it is bound. The Ly49 molecule binds to the MHC-I molecule, thus inhibiting the killing activity of the NK cell. If both signals are activated simultaneously the inhibitory one is dominant and so the cell is not killed.

Many viruses inhibit

the production or expression of the MHC-I molecule. This is entirely logical

as the killing of the virus by cytotoxic T-cells depends upon the MHC-I molecule

presenting viral antigen. One example of this is the adenovirus E3 that produces

a glycoprotein that sequesters MHC-I molecules in the endoplasmic reticulum

and thus prevents their expression on the cell surface. This is where NK cells

function. In the absence of the MHC molecule, there is no signal to override

that of the NKR-P1 molecule and hence the killing action of the NK cell is

activated and the cell not expressing MHC-I will be killed. It is possible

that NK cells act against tumour cells in the same way, by inducing killing

in response to the down-regulation of MHC molecules.

Interferon a and b are produced by many cells in response to viral infection and

have two important actions. Firstly, they enhance the activity of NK cells

by between 20 and 100 fold. The cytokine IL-12 (also known as NK cell-activating

factor) has a similar and synergistic effect. Secondly, they increase the expression of MHC-I thereby enhancing the activity

of cytotoxic T-cells.

The interferon levels

rise immediately after infection. The killing of virally infected cells by

T-lymphocytes takes 2-3 days to commence and does not reach its peak until

7-8 days after the initial infection. Natural Killer Cells fill this gap and

kill infected cells in the first 5-6 days of infection before the cytotoxic

T-cells are active.

NK cells also interact

with antibodies. Antibodies are generally not important in fighting viral

infections. Most of the killing of viruses is done by the cytotoxic T-cells.

However antibodies do act in two ways. The first is that antibodies will bind

to the surface of a virus in the body. In some cases the surface antigen that

the antibody binds will be vital for the viral entry into cells and thus the

antibody will inactive the virus and prevent it from infecting cells. The

second method is known as antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity.

In some cases an infected cell will express on its surface viral antigens

that are recognised by antibodies. The binding of these antibodies triggers

NK cell to kill the infected cell because the NK cells have Fc

receptors.